The expansion of Salesian missionaries in Argentina during the second half of the 19th century is retraced, in a country open to foreign capital and characterized by intense Italian immigration. Legislative reforms and a shortage of schools favored the educational projects of Don Bosco and Don Cagliero, but the reality proved more complex than imagined in Europe. An unstable political context and a nationalism hostile to the Church were intertwined with anti-clerical and Protestant religious tensions. There was also the dramatic condition of the indigenous people, pushed south by military force. The rich correspondence between the two religious figures shows how they had to adapt their objectives and strategies in the face of new social and religious challenges, while keeping alive the desire to extend the mission to Asia as well.

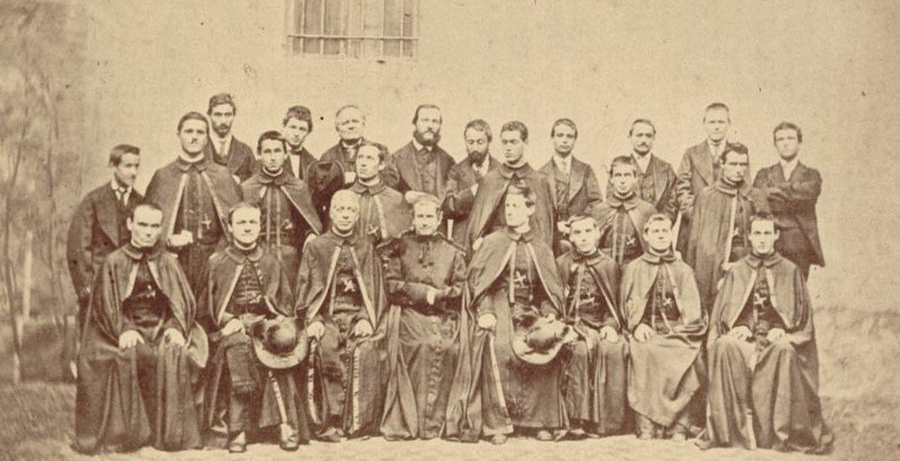

Given the juridical missio received from the pope, the title and spiritual faculties of apostolic missionaries granted by the Congregation of Propaganda Fide, a letter of presentation from Don Bosco to the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, the ten missionaries after a month’s journey across the Atlantic Ocean, in mid-December 1875, arrived in Argentina, an immense country populated by just under two million inhabitants (four million in 1895, in 1914 there would be eight million). They barely knew the language, geography and a little history of the place.

Welcomed by the civil authorities, the local clergy and benefactors, the initial months were happy ones. The situation in the country was in fact favourable, both economically, with large investments of foreign capital, and socially with the legal opening (1875) to immigration, especially Italian: 100,000 immigrants, 30,000 of them in Buenos Aires alone. The educational situation was also favourable due to the new law on freedom of education (1876) and the lack of schools for “poor and abandoned children”, such as those to which the Salesians wanted to dedicate themselves.

Difficulties arose instead on the religious side – given the strong presence of anticlericals, Freemasons, hostile liberals, English (Welsh) Protestants in some areas – and the simple religious spirit of many native and immigrant clergy. Similarly on the political side given the ever looming risks of political, economic and commercial instability, nationalism hostile to the Catholic Church and susceptible to any outside influence, and the unresolved problem of the indigenous peoples of the Pampas and Patagonia. The continuous advance of the southern frontier line in fact forced them further and further south and towards the Cordillera, when not actually eliminating them or, capturing them and selling them as slaves. Fr Cagliero, the expedition leader, immediately realised this. Two months after landing there he wrote, “The Indians are exasperated with the National Government. They go armed with Remingtons, they take men, women, children, horses and sheep as prisoners […] we must pray to God to send them missionaries to free them from the death of soul and body.”

From the utopia of the dream to the reality of the situation

In 1876-1877 a kind of long-distance dialogue took place between Don Bosco and Fr Cagliero: in less than twenty months no fewer than 62 of their letters crossed the Atlantic. Fr Cagliero, who was on the spot, undertook to keep to the directives given by Don Bosco on the basis of the sketchy information available to him and his inspirations from on high, which were not easy to decipher. Don Bosco in turn came to know from his leader in the field how the reality in Argentina was different from what he had thought in Italy. The operational project studied in Turin could indeed be shared in terms of objectives and the same general strategy, but not in the geographical, chronological and anthropological coordinates initially envisaged. Fr Cagliero was perfectly aware of this, unlike Don Bosco who instead tirelessly continued to expand the spaces for the Salesian missions.

On 27 April 1876 in fact he announced to Fr Cagliero that he had accepted a Vicariate Apostolic in India – excluding the other two proposed by the Holy See, in Australia and China – to be entrusted to him, therefore leaving the missions in Patagonia to others. Two weeks later, however, Don Bosco presented a request to Rome to erect a Vicariate Apostolic for the Pampas and Patagonia as well, which he considered, erroneously, to be terra nullius [belonging to no one] both civilly and ecclesiastically. He reiterated this in the following August by signing the lengthy manuscript La Patagonia e le terre australiani del continente americano, written together with Fr Giulio Barberis. The situation was made even more complicated by the Argentine government’s acquisition (in agreement with the Chilean government) of the lands inhabited by the natives, which the civil authorities in Buenos Aires had divided into four governorates and which the Archbishop of Buenos Aires rightly considered subject to his ordinary jurisdiction.

But the furious governmental struggles against the natives (September 1876) meant that the Salesian dream “To Patagonia, to Patagonia. God wills it!” remained just a dream for the time being.

The “Indianised” Italians

In the meantime, in October 1876, the archbishop had proposed to the Salesian missionaries that they take over the parish of La Boca in Buenos Aires to serve thousands of Italians “more Indianised than the Indians as far as customs and religion are concerned” (as Fr Cagliero would write). They accepted it. During their first year in Argentina, in fact, they had already stabilised their position in the capital: with the formal purchase of the Mater Misericordiae chapel in the city centre, with the establishment of festive oratories for Italians in three parts of the city, with the hospice of “artes y officios” and the church of San Carlos in the west – which would remain there from May 1877 to March 1878 when they moved to Almagro – and now the parish of La Boca in the south with an oratory that was being set up. They also planned a novitiate and while they waited for the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians they envisaged a hospice and boarding school in Montevideo, Uruguay.

At the end of 1876 Fr Cagliero was ready to return to Italy, seeing also that both the possibility of entering Chubut and the foundation of a colony in Santa Cruz (in the extreme south of the continent) were being excessively prolonged due to a government that was creating obstacles for the missionaries and that would have preferred, where the native were concerned, “to destroy them rather than place them in redcutions”.

But with the arrival in January 1877 of the second expedition of 22 missionaries, F Cagliero independently planned to attempt an excursion to Carmen de Patagones, on the Río Negro, in agreement with the archbishop. Don Bosco in turn the same month suggested to the Holy See that three Vicariates Apostolic (Carmen de Patagones, Santa Cruz, Punta Arenas) be erected or at least one in Carmen de Patagones, committing himself in 1878 to accepting the Vicariate of Mangalor in India with Fr Cagliero as Vicar. Not only that, but on 13 February with immense courage he also declared himself available, again in 1878, for the Vicariate Apostolic of Ceylon in preference to one in Australia, both proposed to him by the Pope (or suggested by him to the Pope?). In short Don Bosco was not satisfied with Latin America, to the west, he dreamed of sending his missionaries to Asia, to the east.

If Patagonia must wait… let’s go to Asia

🕙: 5 min.