The 150th anniversary of the Salesian missions will be held on November 11, 2025. We believe it might be interesting to offer our readers a brief history of what has gone before and early stages of what was to become a kind of Salesian missionary epic in Patagonia. We will do so over five episodes, with the help of unpublished sources that allow us to correct the many inaccuracies that have passed into history.

Let us clear the field immediately: it is said and written that Don Bosco wanted to leave for the missions both as a seminarian and as a young priest. This is not documented. While, as a 17 year old student (1834) he applied to join the Franciscan Reformed friars at the Convent of the Angels in Chieri who had missions, the request was apparently made mainly for financial reasons. If ten years later (1844), when he left the “Convitto” in Turin, he was tempted to enter the Congregation of the Oblates of the Virgin Mary, who had just been entrusted with missions in Burma (Myanmar), it is however also true that a missionary vocation, for which he had perhaps also undertaken some study of foreign languages, was only one of the possibilities of apostolate for the young Don Bosco that opened up before him. In both cases Don Bosco immediately followed the advice, first of Fr Comollo to enter the diocesan seminary and, later, of Fr Cafasso to continue to dedicate himself to the young people of Turin. Even in the twenty years between 1850 and 1870, busy as he was in planning the continuity of his “work of the Oratories”, in giving a juridical foundation to the Salesian society he was setting up, and in the spiritual and pedagogical formation of the first Salesians and all young people from his Oratory, he was certainly not in a position to follow up on any personal missionary aspirations or those of his “sons”. There is not even a hint of him or the Salesians going to Patagonia, although we see this in writing or on the web.

Heightening missionary sensitivity

This does not detract from the fact that the missionary sensitivity in Don Bosco, probably reduced to faint hints and vague aspirations in the years of his priestly formation and early priesthood, sharpened considerably over the years. Reading the Annals of the Propagation of the Faith gave him good information on the missionary world, so much so that he drew episodes from them for some of his books and praised Pope Gregory XVI who encouraged the spread of the Gospel to the far corners of the earth and approved new religious Orders with missionary aims. Don Bosco could have received considerable influence from Canon G. Ortalda, director of the diocesan Council of the Propaganda Fide Association for 30 years (1851-1880) and also promoter of “Apostolic Schools” (a sort of minor seminary for missionary vocations). In December 1857 he had also launched the project of an Exposition in favour of the Catholic Missions entrusted to the six hundred Sardinian Missionaries. Don Bosco was well informed about it.

Missionary interest grew in him in 1862 at the time of the solemn canonisation in Rome of the 26 Japanese protomartyrs and in 1867 on the occasion of the beatification of more than two hundred Japanese martyrs, also celebrated with solemnity at Valdocco. Also in the papal city during his long stays in 1867, 1869 and 1870 he was able to see other local missionary initiatives, such as the foundation of the Pontifical Seminary of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul for foreign missions.

Piedmont with almost 50% of Italian missionaries (1500 with 39 bishops) was in the vanguard in this field and Franciscan Luigi Celestino Spelta, Apostolic Vicar of Hupei, visited Turin in November 1859. He did not visit the Oratory, instead Fr Daniele Comboni did so in December 1864, publishing his Plan for Regeneration for Africa in Turin with the intriguing project of evangelising Africa through Africans.

Don Bosco had an exchange of ideas with him. In 1869 Comboni tried, unsuccessfully, to associate him with his project and the following year invited him to send some priests and lay people to direct an institute in Cairo and thus prepare him for the missions in Africa, at the centre of which he counted on entrusting the Salesians with an Apostolic Vicariate. At Valdocco, the request, which was not granted, was replaced by a willingness to accept boys to be educated for the missions. There, however, the group of Algerians recommended by Archbishop Charles Martial Lavigerie found difficulties, so they were sent to Nice, France. The request in 1869 by the same archbishop to have Salesian helpers in an orphanage in Algiers in times of emergency was not granted. In the same way, the petition by Brescian missionary Giovanni Bettazzi to send Salesians to run an up-and-coming institute of arts and trades, as well as a small minor seminary in the diocese of Savannah (Georgia, USA) was suspended from 1868. Proposals from others, whether to direct educational works in “mission territories”, or direct action in partibus infidelium, could also have been attractive, but Don Bosco would never give up either his full freedom of action – which he perhaps saw compromised by the proposals he had received – or above all his special work with the young, for whom he was at the time very busy developing the newly approved Salesian Society (1869) beyond the borders of Turin and Piedmont. In short, until 1870 Don Bosco, although theoretically sensitive to missionary needs, was cultivating other projects at a national level.

Four years of unfulfilled requests (1870-1874)

The missionary theme and the important questions related to it were the object of attention during the First Vatican Council (1868-1870). If the document Super Missionibus Catholicis was never presented in the general assembly, the presence in Rome of 180 bishops from “mission lands” and the positive information about the Salesian model of religious life, spread among them by some Piedmontese bishops, gave Don Bosco the opportunity to meet many of them and also to be contacted by them, both in Rome and Turin.

Here on 17 November 1869 the Chilean delegation was received, with the Archbishop of Santiago and the Bishop of Concepción. In 1870 it was the turn of Bishop D. Barbero, Apostolic Vicar in Hyderabad (India), already known to Don Bosco, who asked him about Sisters being available for India. In July 1870 Dominican Archbishop G. Sadoc Alemany, Archbishop of San Francisco in California (USA), came to Valdocco. He asked, successfully, for the Salesians for a hospice with a vocational school (which was never built). Franciscan Bishop L. Moccagatta, Apostolic Vicar of Shantung (China) and his confrere Bishop Eligio Cosi, later his successor, also visited Valdocco. In 1873 it was the turn of Bisop T. Raimondi from Milan who offered Don Bosco the possibility of going to direct Catholic schools in the Apostolic Prefecture of Hong Kong. The negotiations, which lasted over a year, came to a standstill for various reasons, just as in 1874 did a project for a new seminary by Fr Bertazzi for Savannah (USA) also remain on paper. The same thing happened in those years for missionary foundations in Australia and India, for which Don Bosco started negotiations with individual bishops, which he sometimes gave as a fait accompli to the Holy See, while in reality they were only projects in progress.

In those early 1870s, with a staff consisting of little more than two dozen people (including priests, clerics and brothers), a third of them with temporary vows, scattered across six houses, it would have been difficult for Don Bosco to send some of them to mission lands. All the more so since the foreign missions offered to him up to that time outside Europe presented serious difficulties of language, culture and non-native traditions, and the long-standing attempt to have young English-speaking personnel, even with the help of the Rector of the Irish college in Rome, Msgr Toby Kirby, had failed.

(continued)

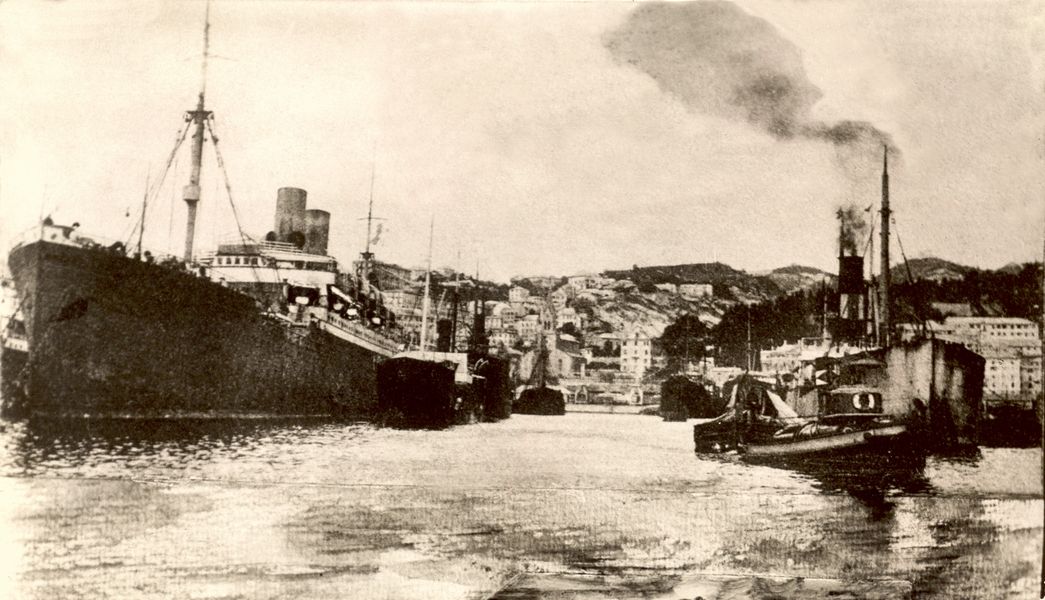

Historic photo: The Port of Genoa, November 14, 1877.